Feature Story

More feature stories by year:

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

Return to: 2016 Feature Stories

Return to: 2016 Feature Stories

CLIENT: LA CONSULTING

Aug. 23, 2016: Water Online

By Khalid Bazmi, PE, assistant director/county engineer, County of Orange; Phil Lauri, PE, assistant general manager, Mesa Water District; and Harry Lorick, principal, PE, PWLF, LA Consulting, Inc.

By Khalid Bazmi, PE, assistant director/county engineer, County of Orange; Phil Lauri, PE, assistant general manager, Mesa Water District; and Harry Lorick, principal, PE, PWLF, LA Consulting, Inc.

Public works managers often strive to improve their performance and optimize resources. One way to achieve this is to follow the process of becoming a high-performance organization (HPO). Such a designation is defined by the HPO Center by achieving financial and non-financial results that are exceedingly better than those of a peer group over a five-or-more-year period of time (De Waal, 2012). This article describes an HPO and the related advantages. Two examples are provided: one is an agency functioning as an HPO and of the other is striving to become one. The concepts in this effort are outlined and can be applied to any public works organization.

The HPO framework is not a set of instructions or a recipe that can be followed blindly. Rather it is a framework that has to be translated by managers to their specific organizational situation in their current time, by designing a specific variant of the framework fit for their organization. This framework was developed from an evaluation of 1,470 organizations in 50 countries where statistical analysis of the collected data showed that there are 35 characteristics in five groups that have a direct positive relation with competitive performance. This further defines that when an organization scores higher on these five HP factors than their peer group, it is classified as an HPO (De Waal, 2012).

The benefits of operating as an HPO are many and allow public works agencies to accomplish not only financial success, but also to improve processes which help to build morale, organizational structure, and communication between employees. A successful transition into an HPO begins with a strong commitment from senior management along with a culture of engagement throughout the organization. The process takes place over a period of five years or more and is accomplished by "focusing in a disciplined way on what really matters to the organization" (De Waal, 2012). Strong leadership, vision, and values are key factors to creating an environment in which all personnel are inspired to work towards and realize the benefits of becoming an HPO.

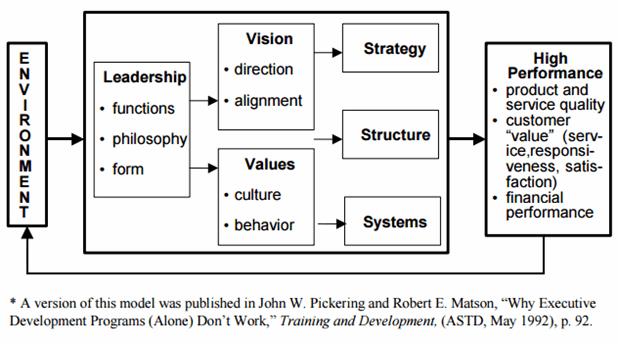

Figure 1 from Pickering & Matson (1992) outlines a general approach for agencies transitioning into an HPO system. Initial steps include the identification of present and future financial responsibilities along with the review of general mangement policies. An understanding of current and desired functions, policies, and culture should be clearly identified before moving forward. From here, an agency can begin to put in place a new vision and set of values that reflect HPO specific work culture and goals. With a refreshed culture and a focused direction, the next step is to implement a revised strategy and structure. Appropriately, agencies can expect improvements in many aspects of their daily and long-term operations including improved product quality, customer service, productivity, and financial performance. One of the most crucial functions of any HPO is the continued evaluation of results and subsequent benchmarking with other HPOs. Monitored results and other environmental factors should be taken into consideration throughout the process of continuous improvement.

Figure 1. HPO General Approach

Traditional organizations are often comprised of "top-down" control structures. These bureaucratic hierarchies can lead to inefficient and repetitive communication chains. Within the structure of traditional agencies, job roles are specialized and narrowly defined. All of these factors can lead to a rigid framework incapable of adaptation. In contrast, an HPO consists of autonomous and self-regulating work units. Employees have direct communication with decision-makers and information is transparent and easily accessible. One of the key tools an HPO has at its disposal is documentation. An agency-wide understanding of core processes and procedures allows for informed and proactive decision-making at all levels. An HPO is able to gauge successes and failures more accurately through the collection of highly detailed data. Insight from data is communicated more directly through streamlined communication channels and the removal of bloated organizational structures. As a result, the HPO can identify and solve problems more quickly and efficiently.

Two California public works agencies operating at different levels of efficiency both set a goal to function as high-performance organizations. Following the outlined steps, they were able to identify and execute the key values, processes, and strategies required to achieve these goals. As a rule, no agency should expect to make a transition without some adversity. The initial efforts presented each agency with unique hurdles and, as with many large-scale implementations, the cost versus benefit was at times challenged by various stakeholders. In these moments, continuous commitment from leadership advanced the realization of sustainable and lasting changes. As a result, these agencies are now far better suited to withstand shifts in organizational structure, updates in technology and processes, and other unforeseen challenges. An HPO saves money, works more efficiently, creates more satisfied personnel, and is able to clearly define and succeed in achieving goals which result in customer satisfaction. The details of these implementations speak for themselves.

Orange County Public Works Department is an agency strongly committed to becoming an HPO and is well on its way with plans in near future to being identified as a HPO. OC Public Works understands the challenges that can be expected in transitioning to a new system and how a proactive process can help achieve measurable results almost immediately.

OC Public Works services 790 square miles and a population of over 3.1 million people. The agency is responsible for 320 road miles and over 380 flood channel miles. Before committing to their HPO mission, the agency dealt with many of the issues that affect public works agencies of all sizes and varieties. A one-to-one communication system style was in place which led to redundancy and slow reaction times. Often, this hindered the agency's ability to respond to unexpected high-priority work orders as well as customer complaints. This communication system was a cause of frustration for employees and created a culture of disconnection within the organization. The experience of documenting core processes and procedures was not easily accessible between divisions, and work units found they were unable to access key information.

In order to improve their process, the agency committed itself to establishing a culture that valued leadership and strong direction. They identified priorities such as increased utilization of resources, automation of tasks, and identification of assets. Their vision was to provide excellent, innovative, and professional public works projects and services to their community. In its quest to become an HPO, the agency improved with new leadership, a new organizational structure, and an update in technological resources which continues today. All of this was in a bid to better serve both customers and employees.

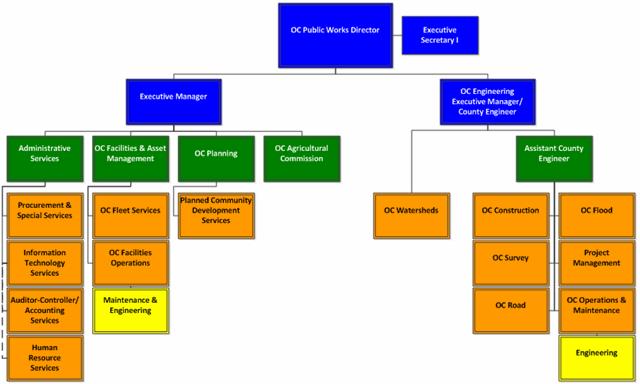

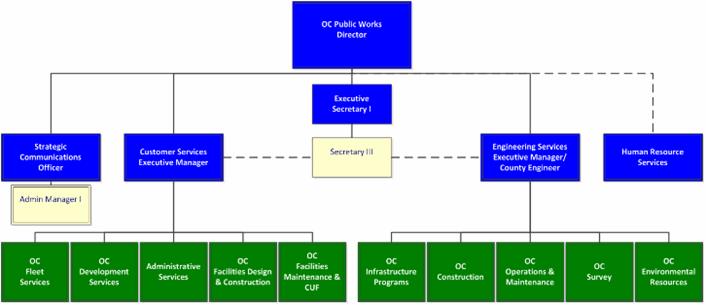

Following HPO guidelines, the agency phased out its conventional organizational structure (Figure 2) and implemented a wider span of control (Figure 3). This change simplified communications and avoided redundancy by streamlining hierarchies. Employees received training to acquire a broader range of skills, which led to more fluid departments. Rather than one-to-one reporting relationships and redundant linear communication, staff members were able to view a snapshot of scheduled tasks, assets, and goals and reported issues department-wide. Over the last six months, OC Public Works implemented a "one-stop shop" project management system to streamline the capital improvement program, utilized resource loading tools to balance current and future work load, as well as utilized alternative project delivery such as construction manager at risk (CMAR), design-build, and job order contracting (JOC) to deliver capital and maintenance projects faster and cheaper. The county surveyed staff in two areas: alternate work schedules and director's employee engagement survey. They also started reaching out to line staff via monthly coffee meetings within each of the 10 service areas to create direct lines of communication and engage employees at all levels. As a result, employees are now engaged in the mission to improve morale, increase efficiency, and improve customer service.

Figure 2. Narrow Span Of Control

Figure 3. Wide Span Of Control

For OC Public Works, the restructuring of the agency, along with a commitment to improving technology and company culture, has already helped the agency realize annual countywide savings of $1.6 million and departmental savings of $7 million. Going forward, the department has set initiatives to create partnerships with staff and to implement a "bottom-up" style of management. The agency realizes that continued success and process refinement is also dependent upon internal and external benchmarking. The value of comparing the agency's metrics to other HPOs is most important as it gives the agency a sense of where its performance measures stand in comparison to organizations with the same goals of excellence and success. Currently Orange County is in the early stages of establishing various key metrics. OC Public Works has set a goal to continuously surpass benchmarks of similar agencies over an extended period of time.

While OC Public Works continues to take the steps required to become an HPO, another organization, Mesa Water District, operates with that distinction.

When initiating the core tenets of a high-performance organization, it is important to remember that one approach does not fit all. Organization size, management structure, technology, resources, and processes are some of the key factors impacting an approach. Mesa Water District is a mature functioning HPO, currently servicing 110,000 customers within an 18-square mile area. Its service area includes Costa Mesa, parts of Newport Beach, and some unincorporated sections of Orange County, including the John Wayne Airport. The district, governed by a five-member board of directors, is responsible for 23,786 water meters, 350 miles of distribution lines, two reservoirs, seven active well sites, and the Mesa Water Reliability Facility (MWRF). Mesa Water® has had many years of accomplishment as an HPO. Among key areas of success are providing 100 percent local water reliability, low water loss, low customer cost without hidden charges, high system integrity, and accepted public support. Mesa Water is the only agency in Orange County that delivers 100 percent local water compared to other agencies in the county which must buy and import water, leading to increased volatility and costs. The water loss of 4.1 percent by the district is in the top 10 percent in American Water Works Association (AWWA) national benchmarks.

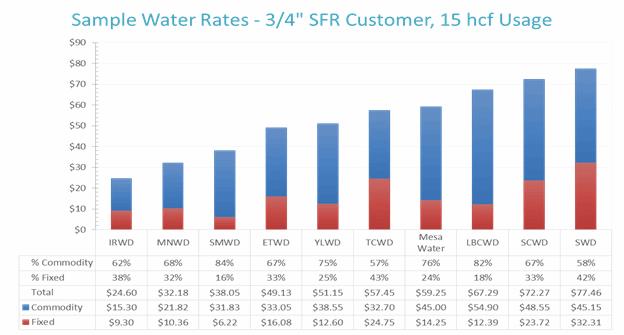

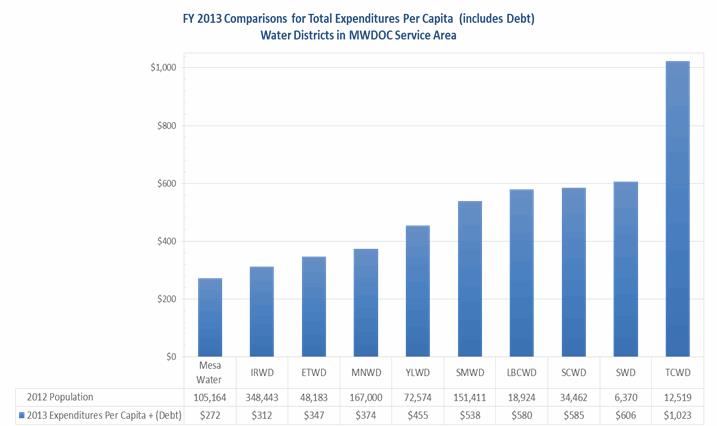

The district's success in customer service and finances can be seen in Figures 4 and 5. Figure 4 depicts how Mesa Water rates are lower than other benchmark agencies in Orange County. Other values provided to customers are shown in Figure 5 as total expenditures per capita, which is the lowest among potable water providers in Orange County.

Figure 4. Mesa Water Rates

Source: Orange County Water Suppliers Water Rates & Financial Information

(Updated as of August 2013) by Municipal Water District of Orange County

Figure 5. Total Expenditures Per Capita

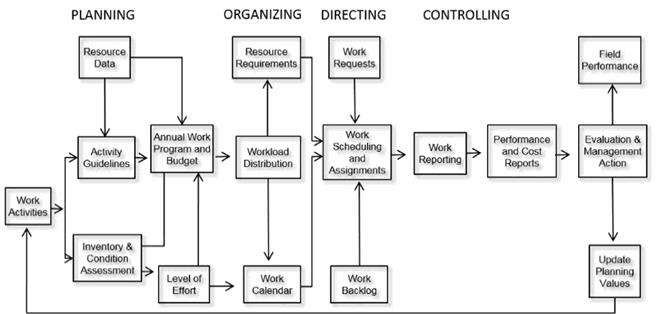

During Mesa Water's initial effort to become an HPO, the agency defined clear and concise operational goals. In determining priorities for the district, Mesa Water outlined seven strategic benchmark goals which would directly reflect their values and ensure high performance, both internally and externally. The agency's ability to create a plan of action was coordinated with an up-to-date computer maintenance management system (CMMS) which allowed for documentation of past work performed and an ability to project future work. Mesa Water followed the principle that, while significant goals often represent only 20 percent of work, they regularly account for 80 percent of a department's output. Key to Mesa Water's success was its implementation of the four basic principles of maintenance management (planning, organizing, directing, and controlling) which are outlined by the American Public Works Association (APWA) (2011) in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Principles Of Maintenance Management

The implementation of technology remains pivotal to Mesa Water's ability to operate at a high level of efficiency. The automated management approach is used to assist in all four principles of maintenance management. As a result, planning can be executed through the monitoring of tasks and work activities. The agency documents work processes along with labor and equipment rates for the purpose of establishing and monitoring guidelines. In evaluating accomplishments and production, they are better able to assess the capabilities of work groups and assets when creating their annual plan. As a result, organization is improved by determining which resources are available to meet the workload. The ability to view data in a clear and concise manner allows Mesa Water to realistically project its needs and determine work on a monthly basis. Work requests, scheduling and assignments can be submitted and processed through a fluid communication plan. Finally, performance and cost reports along with other benchmark information can be viewed in real time, allowing for proactive planning and adaptation.

All data that affects performance is documented, easy to access, and understand. Various team members are able to view financial and management reports. Management frequently engages in dialogue with employees. While the benefits to such a streamlined organization are numerous, perhaps one of the most explicit is that of culture. The organization is able to retain highly skilled employees with technical knowledge, which translates into financial success and satisfied customers. One area of Mesa Water success is measured in a customer survey. A study of 509 customers found 95 percent confidence (+/- 4.3 percent) in the following areas:

Achievement of a safety milestone also demonstrates success. In August 2016, Mesa Water reached three years (1,095 days) without a lost-time accident. This is a result of the board of directors and management making safety a priority. A continuous improvement process has enabled the water district to improve all aspects of operations through focused attention on safety techniques, new or improved policies, staff training, and monthly discussions on the topic. An annual audit helps track progress and identifies areas for improvement. These results demonstrate Mesa Water's ability to provide customers with high-quality service. The agency's success as an HPO manifests itself as an engaged and satisfied public.

The efforts of both OC Public Works and Mesa Water demonstrate how the transition to an HPO can have positive impacts across all areas of an organization. In pursuit of an HPO designation, OC Public Works continues to improve its efforts both internally and externally. Since achieving its HPO status, Mesa Water continues to provide water more effectively and abundantly than regional competitors. Both agencies have seen great improvements in their business systems, processes, and methods through the effective use of best management practices.

For an agency unsure of committing to an HPO transition, it is important to remember that the benefits can be seen almost immediately. Yet, it is a five-year minimum as outlined by De Waal (2012) before an agency can be foreseen as operating as an HPO. However, the organization can expect to discover value and sources of untapped potential from the outset. Initial steps such as performance documentation allow an agency to view its strengths and weaknesses clearly and create a benchmark foundation from which it can identify opportunities to improve. A commitment from leadership sets an example for employees organization-wide and can enrich an agency with a strong vision. By including all staff members in the process from day one, employees' attitudes often shift as their involvement creates an invested success in the process. Throughout the transition, agencies can expect to reap the rewards when they invest in the work and strive to become a high-performance organization. Organizational leaders can expect continuous improvement for years to come when they make the decision to improve an agency through defined goals, strong leadership, and open communication.

Image credit: "Magnolia water tank, 1950," © Seattle Municipal Archives 1950, used under an Attribution 2.0 Generic license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Return to: 2016 Feature Stories