Feature Story

More feature stories by year:

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

![]() Return to: 2018 Feature Stories

Return to: 2018 Feature Stories

CLIENT: EMMES REALTY SERVICES

Aug. 3, 2018: The San Diego Union-Tribune

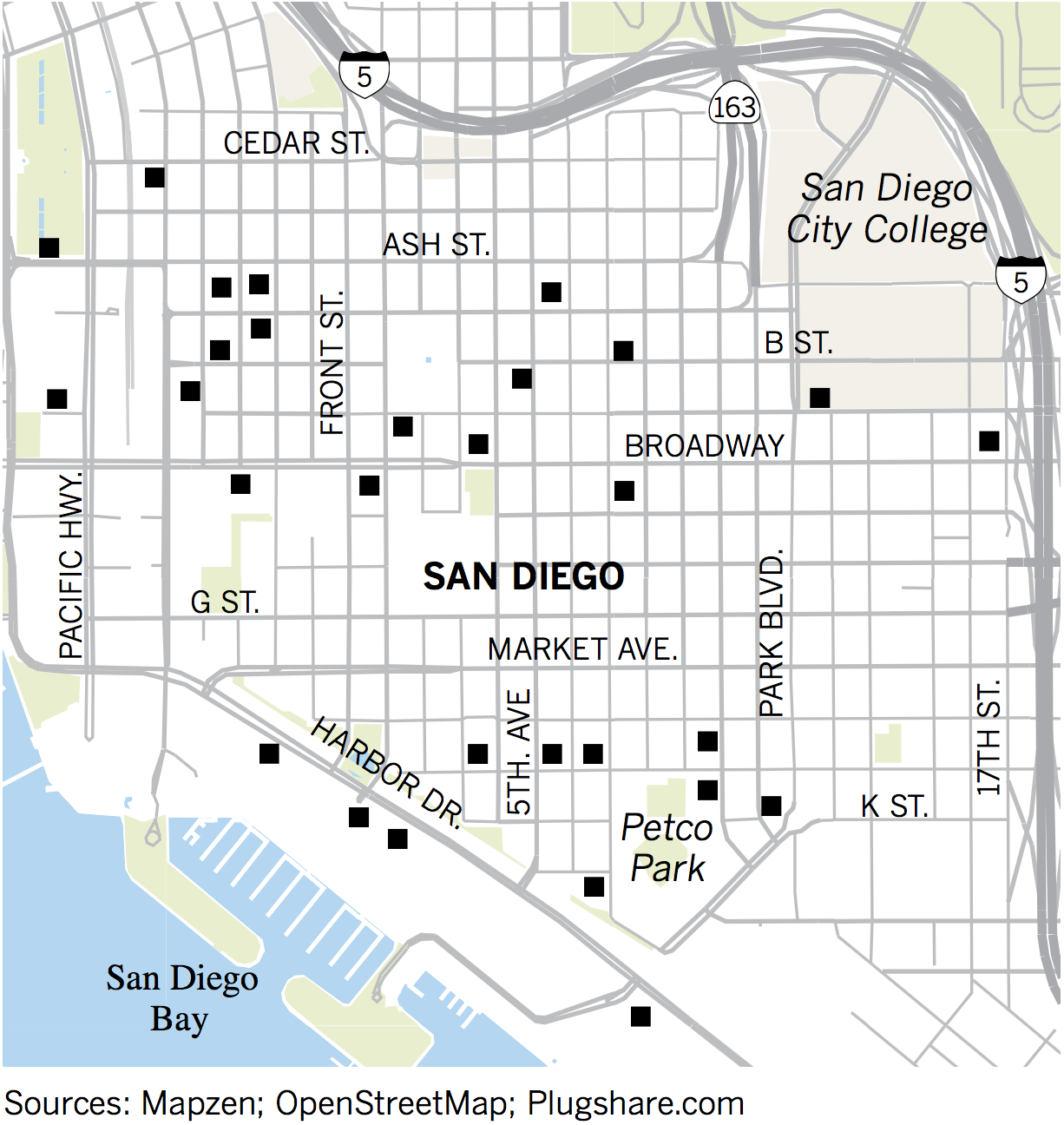

Rodolfo Rodriguez was delighted to discover a brand new Tesla charging location in downtown San Diego.

“Anytime you can find charging, anywhere, it’s great,” Rodriguez said after he plugged in his 2018 Model X on the ground floor of the 6th & A Parking Garage. The owner of the covered garage, EMMES Realty Services, partnered with Elon Musk’s company to install 16 parking spaces, each with dedicated Tesla Superchargers that provide consistent charging times of around 30 to 45 minutes for most drivers.

That’s considerably faster than the eight to 15 hours it takes to charge at what is called a “Level 1” station, primarily for overnight, at home charging, and the three to eight hours needed at a “Level 2” charging station while on the road.

And the new downtown facility makes life a lot easier for Tesla drivers like Rodriguez. Before, the only Tesla supercharging facility was located some 14 miles north of downtown, at the parking lot at Qualcomm’s headquarters in Sorrento Valley.

“Even if you manage to get up there, you’ve got traffic involved, so you never know,” Rodriguez said.

The 6th & A Parking Garage is an example of the growing need for more electric vehicle charging stations, especially in densely populated urban areas, as the EV market tries to meet the ambitious — and expensive — goals set by California policymakers to morph the transportation system from the internal combustion engine to electric-powered vehicles.

“Electric vehicles are one of the best ways to get (greenhouse gas) emissions down, but we need somewhere to charge them,” said Kevin Wood, transportation specialist at the Center for Sustainable Energy, the San Diego-based nonprofit that administers the state’s rebate program for clean cars.

It’s difficult to say how many charging stations have been installed in the private homes of EV owners in the San Diego area but when it comes to public locations, as of last month, San Diego Gas & Electric counted 1,332 Level 2 stations and 111 direct-current, fast charging nozzles in the utility’s service area that includes a portion of Orange County.

That may sound like a lot but officials at the Center for Sustainable Energy say if Gov. Jerry Brown’s goal of 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles on the state’s roads by 2025 becomes a reality, San Diego would need between 8,000 to 14,000 charging ports up and running.

“It’s an eight to 10-fold increase in the next few years in the number of charging stations,” Wood said.

And earlier this year, in his final State of the State address, Brown upped the ante considerably, signing a new executive order — 5 million zero-emission vehicles by 2030. The state is currently at 421,000.

Two years ago, SDG&E unveiled its “Power Your Drive” program to install charging stations at multi-family homes and workplaces. To date, the utility has put in more than 800 chargers and have another 150 under construction. By the middle of next year, SDG&E expects to have about 3,000 chargers installed. The program is funded by ratepayers.

In many ways, EV adoption has largely been a suburban phenomenon, with owners plugging in the garages of their homes.

But for people who live in apartments and condominiums, simply finding a place to charge their EVs can be so difficult that it sometimes keeps them from even considering buying a car that requires a plug-in. A lucky few work for companies that have installed charging stations in their employee parking lots but more often than not, urban EV owners are on their own.

“It is definitely a barrier to entry,” said Jeremy Acevedo, pricing and industry analyst for Edmunds.com. “Having readily available charging networks, I think that’s critical for mass adoption” of EVs.

Parking facilities in existing buildings create other problems. Since many underground parking lots at businesses, apartment complexes and condominiums were built before the EV market even came into existence, installing charging stations can take time and money.

Electrical transformer upgrades are often needed for some charging stations that involve multiple parking spaces.

Officials at Tesla and EMMES worked in coordination with SDG&E to install the 16 supercharging stations at the 6th & A Parking Garage.

“There’s new SDG&E facilities here that are supporting this infrastructure because 16 chargers is a lot of load,” said Todd Cahill, SDG&E Director of Business Services.

Officials at Tesla and EMMES would not disclose how much the 6th & A project cost.

Prices can vary widely, depending on size of the project and the complexity involved. In addition to transformer upgrades, some projects may require trenching and boring, which analysts say can sometimes drive the cost into six figures.

Wood said some charging stations at the Fashion Valley Mall parking lot in Mission Valley came in at a low price because it could run conduit for the wires on the ceiling or on the walls, versus having to dig down through the concrete.

An EV charging stations at the Fenton Market Place in Mission Valley. (John Gibbins / San Diego Union-Tribune)

By contrast, a lot of new construction already takes EV charging infrastructure into account.

The most recent iterations of the California building codes call for commercial parking lots of 10 spaces or more and multi-family buildings of 17 units or more to include charging facilities.

And an increasing number of builders want to put in charging stations as a way to attract younger or more affluent residents.

“A lot of things that are erected now have the foresight to apply and kind of bake it into the design,” Acevedo said. “Doing it the other way around definitely does seem like a costly venture.”

California leads every other state in EV adoption by a wide margin. In 2016, the number of plug-in vehicle registrations per thousand in California was 6.65, more than double the state in second place, Washington (3.04), according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

The state is also spending a lot of money in the process:

All told, that’s about $2 billion largely earmarked for charging stations.

“To really kick-start this market, we do need this investment now,” Wood said.

The state also funds rebates for Californians to buy zero-emissions vehicles through the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project. In an effort to encourage people of more modest incomes to buy or lease clean cars, policymakers in 2016 tweaked the state’s rebate program.

People with household incomes less than or equal to 300 percent of the federal poverty level receive $4,500 for buying or leasing battery-electric vehicles, $3,500 for plug-in hybrids and $7,000 for fuel cell vehicles.

That’s $2,000 more than the standard rebate amounts.

Three hundred percent of the poverty level translates into gross income for an individual of $36,420 or less, or a family of four earning under $75,300.

At the same time, the state made it harder for high-income earners to get rebates, eliminating them for those whose income exceeds $150,000 for single tax filers, $204,000 for head of household filers and $300,000 for joint filers. The caps do not apply for hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles.

A recent study conducted by IHS Markit concluded that 71 percent of the share of buyers of EVs have household incomes of $100,000 or more.

“The state wants to make sure that electric vehicle technology is accessible to all people, especially in low-income communities that often suffer from the worst air pollution,” Wood said.

Wayne Winegarden, senior fellow at the San Francisco-based Pacific Research Institute, which advocates free-market economic policies, doesn’t think all the spending on rebates and charging infrastructure is a good use of public money.

“Right now, we believe the solution to global climate change is lots and lots of electric vehicles — and that might be right, but maybe it’s not,” said Winegarden, who wrote a report criticizing government spending on EVs. “There are so many examples of government getting involved in some industry or company that is going to do something miraculous and 10 years later, either Solyndra goes out of business or ethanol is harming the environment and we’re still subsidizing it.”

Private companies like Tesla are making their own investments in charging stations.

A Tesla official attending the ribbon-cutting for the 16 charging spots at the 6th & A Parking Garage said the facility is part of a larger “urban strategy” for infrastructure projects.

Nate Anderson, Tesla’s regional manager for charging infrastructure in California and Hawaii, said the company will open 10 more stations with about 150 stalls in the greater San Diego area in the next year.

“So you’ll see us in Carlsbad, Del Mar, Escondido, Vista and many, many (other places) in and around San Diego,” Anderson said. “San Diego is actually our fifth-highest concentration of Model 3 reservations in the entire country. So we are stepping up, really investing in the area.”

But Tesla charging stations are designed only for Teslas — so drivers of other EVs, such as a Nissan Leaf or a Chevy Bolt, have to go somewhere else to get a charge.

Can California reach Brown’s goal of 5 million zero-emission vehicles in the space of the next 12 years — and install enough charging facilities to support them?

“That one is tough to say,” Acevedo said. “Even though California has really done a lot of the heaving lifting on EV and plug-in take rate, it’s still a segment that hasn’t fully taken off. We haven’t seen it grow by quantum leaps.”

In recent years, the share of new EV sales in California has only ticked up modestly while sales of gasoline-powered SUVs have taken off — a development due in part to better fuel efficiency by light trucks.

Wood acknowledges the challenges and likens EVs to flat screen televisions, that at one time were expensive and available in limited numbers.

“But now if you go to any electronics store, all you see is flat screen TVs,” Wood said. “And we think somewhere between now and 2030 we might see that same thing happen with electric vehicles, where people … show up at the dealer and all they see is electric vehicles.

“If that does happen, I think we can hit (the 5 million EVs in California) goal but we'll all have to keep working together to make sure we can get all the infrastructure installed to support all those vehicles.”

Return to: 2018 Feature Stories